How Attackers Abuse Signed Drivers to Take Over Infrastructure. Using BYOVD to Bypass PPL Protection Mechanisms in Windows.

A New Era of Kernel Attacks

In the modern cybersecurity ecosystem, attacks on operating system kernels represent one of the most serious threats. By gaining control over the kernel (ring 0), an attacker effectively gains unrestricted power over the system, making it trivial to bypass AV and EDR-class solutions, steal credentials, and conceal their presence.

As we discussed earlier, when using BYOVD techniques, attackers do not look for vulnerabilities in the operating system kernel itself. Instead, they bring along a legitimate, signed third-party driver and exploit vulnerabilities within it to execute code in kernel mode. This allows them to bypass protection mechanisms such as Driver Signature Enforcement (DSE).

In this article, we focus on one of the most important protection mechanisms for user-mode processes in Windows — Protected Process Light (PPL). We examine how it is implemented from the operating system kernel’s perspective and what opportunities attackers have to manipulate PPL when exploiting BYOVD techniques.

Disclaimer

This material is for informational purposes only and is intended for information security professionals, researchers, and system programmers interested in operating system kernel protection mechanisms and defensive system design. Paranoid Security LLC bears no responsibility for any potential damage caused through the use of the information presented. Any activity involving the creation, distribution, or use of computer programs or other computer information knowingly intended for the unauthorized destruction, blocking, modification, or copying of computer information, or for the circumvention or neutralization of information security or protection mechanisms, entails liability in accordance with applicable national legislation.

Process Protection in Windows: The PPL Model

Historically, the Windows security model was built on Discretionary Access Control Lists (DACL) and Access Tokens. This model is fundamental and operates on the principle of: "who" (a process) can perform "what action" (read, write, terminate) on "what object" (a file, another process, a registry key). A process’s access rights are determined by its access token, which is inherited from the user account that launched it. As a result, a user with administrative privileges can control any process in the system — terminate it, debug it, inject code, and so on.

However, this model revealed fundamental limitations:

Administrator privileges are too broad. Malware that gains administrator rights can freely interfere with the operation of any system processes, including those responsible for security (for example, lsass.exe, which stores credentials).

Insufficient isolation of critical components. Even the operating system itself could not fully protect its key processes from "legitimate", yet malicious use of administrative privileges.

With the release of Windows Vista, Microsoft extended the classical security model with the Protected Process mechanism. Its key idea is the introduction of a new, independent authorization factor that is not based on user privileges. The essence of this mechanism is that even if a process has administrator rights, but is not protected, it cannot gain full control over protected processes.

Initially, the Protected Process model was introduced to protect processes related to Digital Rights Management (DRM), such as media playback protection. It created a "digital fortress", isolating key processes from interference, including debugging or termination, even by an administrator.

At all times, processes running under the SYSTEM account (for example, winlogon.exe or lsass.exe) have been prime targets for attackers. By gaining access to such processes, attackers could escalate privileges, bypass security mechanisms, establish persistence, and obtain credentials of other users. Over time, Microsoft extended the Protected Process model to critical operating system components and security software.

With the release of Windows 8.1 (Windows Server 2012 R2), Microsoft introduced an enhanced model — Protected Process Light (PPL). Unlike the binary Protected Process model, PPL introduced a flexible hierarchy of trust levels that determine who can protect or inspect whom. The key improvement was a signature level system, where each protected process and each process attempting to access it must have an appropriate digital signature level (trust level). This creates a structured protection hierarchy in which a process with a higher level can access a process with a lower level, but not vice versa.

Currently, the PPL model is actively used to protect critical Windows components and third-party software:

Credential protection. The lsass.exe process in Windows 11 runs by default with the PsProtectedSignerLsa-Light trust level, making credential and Kerberos ticket theft significantly more difficult.

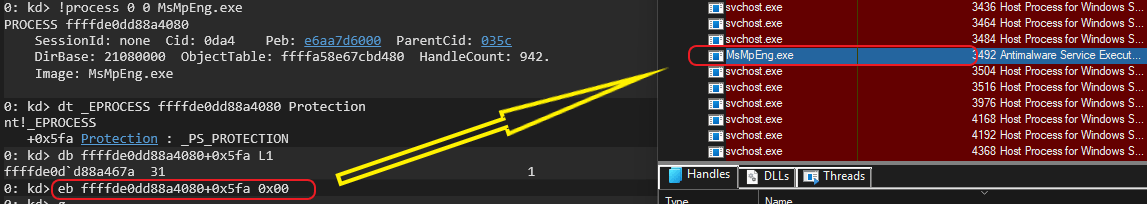

Self-protection of security solutions (AV/EDR classes solutions). The MsMpEng.exe process runs with the PsProtectedSignerAntimalware-Light trust level, significantly complicating attempts to "disable" Windows Defender.

All security in Windows is built on an object model, where each resource (process, file, registry key) is an object protected by access control lists (DACL). Before performing any operation on an object, the system requires obtaining a handle through the appropriate API-call:

HANDLE OpenProcess( [in] DWORD dwDesiredAccess, [in] BOOL bInheritHandle, [in] DWORD dwProcessId );The key parameter is dwDesiredAccess, a bitmask that specifies which operations the requesting process intends to perform on the object (another process): PROCESS_TERMINATE, PROCESS_VM_READ, FILE_WRITE_DATA, and so on.

The verification mechanism works as follows:

- When OpenProcess is called, the system checks the ACL of the target process.

- It compares the rights of the calling process (from its access token).

- If the check passes, a HANDLE with the requested rights is returned.

- All subsequent operations performed through this HANDLE are considered legitimate.

This model assumed that validation at the time of opening the HANDLE was sufficient to ensure security.

With the introduction of Protected Processes and Protected Process Light access to protected processes (from a regular process), can only be obtained with PROCESS_QUERY_LIMITED_INFORMATION access method, which allows retrieving only basic metadata (PID, name, status) and completely blocks memory access and control capabilities.

When a process has a PPL trust level, the Windows kernel applies strict restrictions on which other processes may obtain a HANDLE to it with "critical" rights (such as PROCESS_VM_WRITE, PROCESS_VM_READ, or PROCESS_TERMINATE).

Thus, PPL implements a complex protection hierarchy where a process with a higher trust level can access processes with the same or lower trust level, but not vice versa. In other words, a process can obtain a HANDLE with maximum (or sensitive) access rights to another process only if its trust level is greater than or equal to that of the target process.

BYOVD: A Kernel-Level Perspective

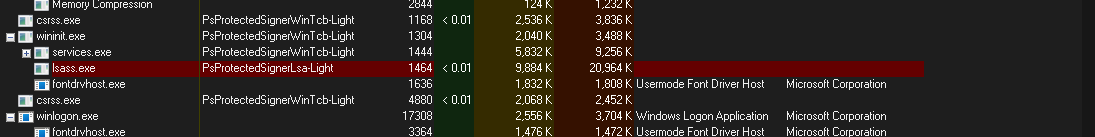

Let us examine the PPL mechanism using an example. If we look at the lsass.exe process in Process Explorer, we will see the following:

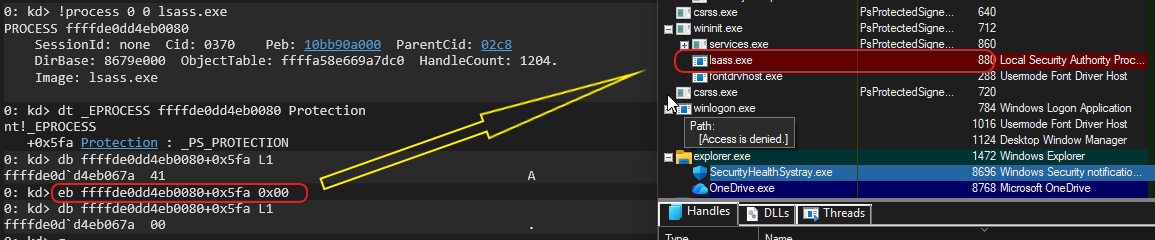

As mentioned earlier, the lsass.exe process has the PPL level PsProtectedSignerLsa-Light. Let us examine the PPL level in more detail. In the kernel, each process is represented by an _EPROCESS structure. This structure contains all information about the running process, including its trust level.

At offset 0x5fa (Windows 11 25H2) there is a one-byte field called Protection, which describes the process trust level (PPL level). The value PsProtectedSignerLsa-Light corresponds to the numeric value 0x41.

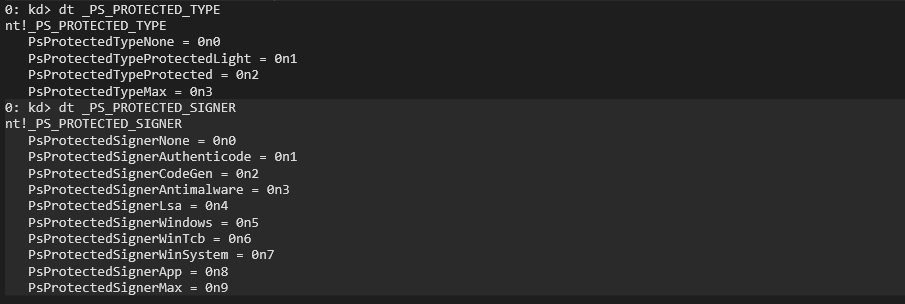

The Protection field has the type _PS_PROTECTION and consists of three fields: Type, Audit, and Signer. Although these fields are undocumented, their purpose is fairly easy to infer.

Audit field enables audit logging.

Type field defines the isolation level of the process. If a process is not protected, this field is set to PsProtectedTypeNone (0x0). In most cases, when a process has PPL protection, this field is set to PsProtectedTypeProtectedLight (0x1).

Signer field defines the trust hierarchy (or “signer level”). For the lsass.exe process (when running as protected), this value is PsProtectedSignerLsa (0x4). For other system processes (wininit.exe, smss, services.exe, etc.), this value is PsProtectedSignerWinTcb (0x6). For antivirus programs (for example, Windows Defender), it is PsProtectedSignerAntimalware (0x3).

Not all PPL processes are equal. There is a hierarchy of protection levels. A process with a lower level cannot access a process with a higher level. Some of the key levels (from highest to lowest) are:

PsProtectedSignerWinTcb (Windows TCB) — used by critical Windows components that must not be interfered with.

PsProtectedSignerLsa (LSA) — used to protect the lsass.exe (Local Security Authority Subsystem Service) process. This prevents administrators and pentesters from directly dumping its memory using tools (such as mimikatz).

PsProtectedSignerAntimalware (Antimalware) — designed for EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) and antivirus solutions. When an EDR process (for example, MsMpEng.exe process of Windows Defender) runs as PPL with this level, even an administrator cannot manipulate its memory or terminate it.

Summarizing the above, processes with the PsProtectedSignerLsa trust level can access PsProtectedSignerAntimalware processes, but not vice versa. Processes with the PsProtectedSignerWinTcb trust level can access both PsProtectedSignerAntimalware and PsProtectedSignerLsa processes, but not the other way around.

Thus, the kernel checks the Protection field in _EPROCESS every time one process attempts to open a HANDLE to another via the NtOpenProcess system call.

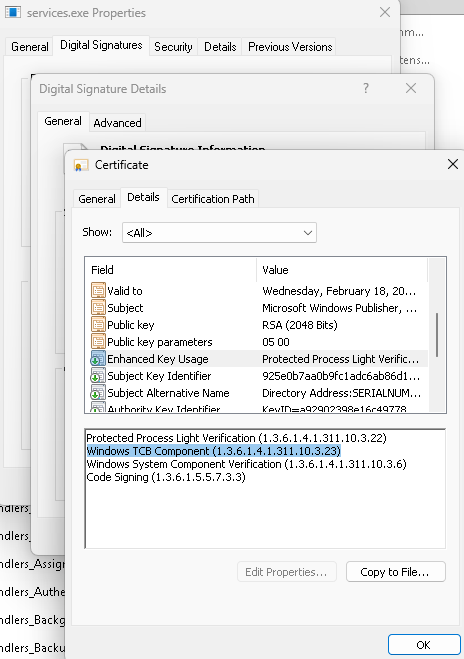

It is also important to note that a process cannot request the operating system to launch it with a desired PPL level. The PPL flag with which an executable file must be launched is embedded in its digital signature — or more specifically, in the extended attributes (Enhanced Key Usage, EKU). For example, to run with the PsProtectedSignerAntimalware level, a binary file must be signed with a special certificate that Microsoft issues only to verified antivirus vendors and system processes must contain the Protected Process Light Verification (1.3.6.1.4.1.311.10.3.22) entry in the EKU attribute.

Examples of BYOVD Technique Exploitation

Attackers who gain kernel access via BYOVD perceive PPL as a single obstacle that can be easily bypassed. Their goal is to manipulate the _EPROCESS structure (specifically, the Protection field) in order to remove PPL protection from a process.

By using a combination of kernel read/write primitives (obtained from a vulnerable driver), the attacker locates the EPROCESS structure of the target process and sets the Protection field to zero, as a result of which the process instantly becomes a regular, unprotected process from the kernel’s perspective. After that, any process with administrative privileges can perform the following actions:

For LSASS: Call the MiniDumpWriteDump and create a full memory dump of lsass.exe, which can then be analyzed using Mimikatz to extract credentials.

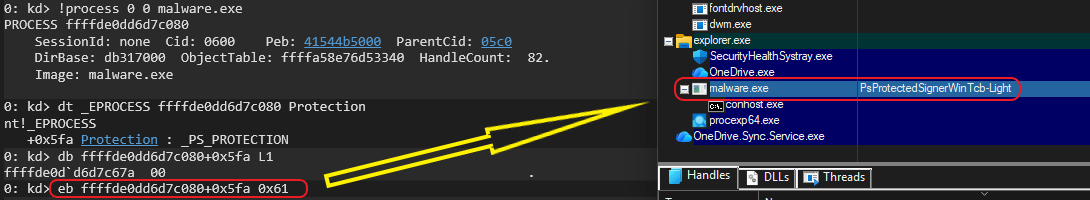

In this example, the debugger command (eb) is used to remove protection from the lsass.exe process, after which it is no longer protected.

For AV/EDR, after removing protection, attackers gain the ability to terminate the process or suspend its execution, effectively disabling protection.

In the same manner as in the previous example, protection is removed from the Windows Defender process.

Another, more elegant method of manipulating PPL is raising the PPL level of a malicious process. Similar to the first approach, using the same kernel read/write primitives, the attacker locates the _EPROCESS structure of their own attacking process and modifies the PPL fields, setting the highest possible level, for example, PsProtectedSignerWinTcb.

As a result, the “attacking process” now has the highest PPL level in the system. According to PPL rules, it can call OpenProcess with full access (PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS) to any other process, including EDR and lsass, since its trust level is now higher than or equal to any other.

Examples of Vulnerable Primitives

In this section, we examine an example of a kernel primitive that enables arbitrary reading from kernel memory, as well as writing to kernel memory. All examples presented are taken from real-world drivers with confirmed CVEs. However, for ethical reasons, we do not disclose the names of these drivers or the CVE identifiers.

Previously, we examined MmMapIoSpace primitive, which, when combined with read and write primitives, allowed arbitrary manipulation of kernel memory. This time, we examine ZwMapViewOfSection primitive, which is essentially just as benign in appearance, yet provides attackers with functionality no less powerful than MmMapIoSpace.

The kernel function ZwMapViewOfSection (paired with ZwOpenSection) can be used to map arbitrary physical memory into the virtual address space of an attacking process. If a vulnerable driver gives the attacker control over the parameters of this function, they can map physical memory containing kernel structures (including _EPROCESS) into their process and modify them from user mode.

The ZwMapViewOfSection function is a Windows kernel primitive designed to project (map) part or all of a section object into the virtual address space of a specified process. Its primary purpose is to provide a flexible and controlled memory management mechanism. Its key capability is memory sharing between processes: a section can be mapped into the address spaces of multiple processes, allowing them to read from and write to the same region of physical memory.

By calling ZwMapViewOfSection, direct access to physical memory can be obtained, making it possible to map specific physical memory ranges. Let us examine the function definition:

NTSYSAPI NTSTATUS ZwMapViewOfSection( [in] HANDLE SectionHandle, [in] HANDLE ProcessHandle, [in, out] PVOID *BaseAddress, [in] ULONG_PTR ZeroBits, [in] SIZE_T CommitSize, [in, out, optional] PLARGE_INTEGER SectionOffset, [in, out] PSIZE_T ViewSize, [in] SECTION_INHERIT InheritDisposition, [in] ULONG AllocationType, [in] ULONG Win32Protect );The function operates exclusively with virtual addresses in the context of the target process. BaseAddress parameter is an input/output virtual address in the target process. On input, it may contain a desired virtual address for mapping, or NULL, in which case the system chooses the address. On output, it contains the actual virtual address at which the section view is mapped in the target process. This address is a valid pointer in the context of that process.

The SectionOffset parameter specifies the offset, in bytes, from the beginning of the section object at which the mapped view will start.

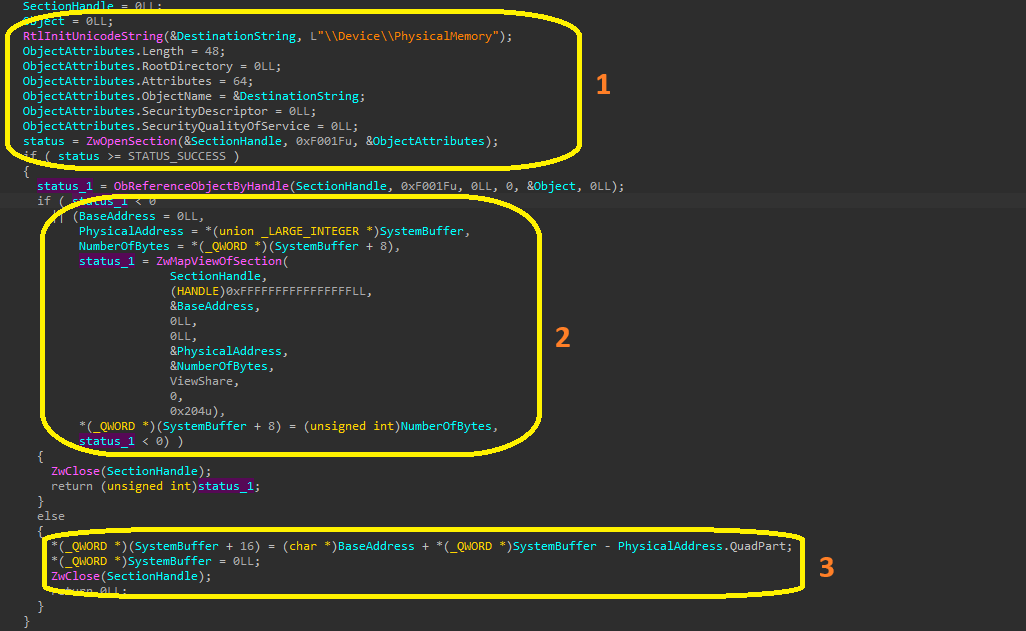

To obtain a section backed by physical memory (\Device\PhysicalMemory), the driver must first open the section (using ZwCreateSection), specifying \Device\PhysicalMemory as the source. It must then call ZwMapViewOfSection, which maps the portion specified by SectionOffset and ViewSize into virtual memory. In this case, SectionOffset contains the physical address. Let us examine an example of a real driver that provides such functionality:

First (1), using the ZwCreateSection call, the driver obtains a handle to the physical memory section by passing its name (\Device\PhysicalMemory) in the ObjectAttributes.

Next (2), it maps the opened section into the address space of the calling process at the physical address PhysicalAddress with a size of NumberOfBytes.

Result in the form of a virtual pointer, is returned in the BaseAddress variable and then passed to user mode (3) of the calling process via SystemBuffer. The 0xF001F value (DesiredAccess) describes the requested access rights. Let us decode this value:

0xF001Fu = STANDARD_RIGHTS_REQUIRED (0xF0000) + SECTION_QUERY (0x1) + SECTION_MAP_WRITE (0x2) + SECTION_MAP_READ (0x4) + SECTION_MAP_EXECUTE (0x8) + SECTION_EXTEND_SIZE (0x10)Passing the 0xF001F mask means requesting full, unrestricted control over the section object.

The danger of this implementation lies in the fact that the driver code performs no validation of allowable physical address ranges, allowing attackers to gain maximum-privilege access to kernel memory.

Defense and Countermeasures

Combating kernel-level attacks is a cat-and-mouse game, but defenders have tools no less powerful than those available to attackers.

Kernel Patch Protection

Kernel Patch Protection (KPP), also known as PatchGuard (PG), is a built-in Windows security mechanism that periodically verifies the integrity of critical kernel structures. If PatchGuard detects that someone (for example, an attacker) has modified the kernel — such as altering _EPROCESS or the System Service Descriptor Table (SSDT) — it immediately triggers a Blue Screen of Death (BSOD). PatchGuard checks at least the following kernel elements:

- System Service Descriptor Tables (SSDT);

- Interrupt Descriptor Table (IDT);

- Global Descriptor Table (GDT);

- Kernel code itself, HAL, and NDIS libraries.

Upon detecting modification, PatchGuard stops the system with the CRITICAL_STRUCTURE_CORRUPTION bug check.

This is a powerful defensive mechanism. By attacking _EPROCESS, an attacker risks "crashing" the system. However, PatchGuard does not run continuously — it executes on a schedule, leaving "a temporary window" of opportunity for attackers. In addition, PatchGuard can be disabled when the system is booted in kernel debugging mode, which is often used by researchers but can also be abused by attackers in certain scenarios. For this reason, monitoring specialists should configure auditing of process creation command-line parameters (WinEventLog 4688 или Sysmon 1) and track, for example, the enabling of kernel debugging mode:

bcdedit /debug onKernel Mode Code Signing

Kernel Mode Code Signing (KMCS) enforces signature verification for all drivers loaded into kernel mode. This mechanism ensures that only drivers from trusted developers can be loaded. Attackers are therefore forced to search for vulnerabilities only in signed, legitimate drivers, narrowing the attack surface. However, this mechanism can be temporarily disabled, and, similar to PatchGuard, this functionality is actively used not only by developers but also by attackers. Therefore, it is advisable to monitor the execution of commands such as:

bcdedit /set testsigning offMitigation

Blocking vulnerable drivers is the most effective method. Microsoft maintains the Microsoft Recommended Driver Block List — a list of drivers known to be vulnerable and abused in BYOVD attacks. Enabling this policy (via Windows Defender Application Control, WDAC) prevents these drivers from being loaded into the kernel, depriving attackers of their primary tool.

Hypervisor-Protected Code Integrity (HVCI) provides kernel isolation. By using Virtualization-Based Security (VBS), Windows creates a protected environment where kernel code integrity checks are performed "outside" of the kernel itself. This significantly increases exploitation complexity by isolating kernel code from potentially compromised processes.

Conclusion

In the modern cybersecurity landscape, protected processes represent an important security mechanism in contemporary versions of Windows, providing isolation for critical system processes regardless of access control lists. However, as the examined attack scenarios demonstrate, the BYOVD technique allows attackers to bypass this protection mechanism by abusing legitimate drivers.

Bring Your Own Vulnerable Driver (BYOVD) is a powerful attack vector in which attackers use legitimate but vulnerable drivers with valid digital signatures to gain unauthorized kernel-level access. These drivers, often developed for low-level system monitoring or hardware optimization, contain vulnerabilities that allow arbitrary kernel memory read/write operations or privileged capabilities.

A successful PPL bypass via BYOVD consists of several stages: obtaining administrative privileges, loading a vulnerable driver, locating and modifying the _EPROCESS structures of target processes, and subsequently performing malicious actions.

Defending against such attacks requires a comprehensive strategy that includes blocking known vulnerable drivers via the Microsoft Recommended Driver Block List (enabled by default in Windows 11), enabling HVCI (Memory Integrity), monitoring suspicious activity, and regularly updating drivers and the operating system.

Understanding PPL mechanisms and methods for bypassing them is critically important for both defenders seeking to maintain system integrity and security professionals engaged in penetration testing and malware analysis. Awareness of these techniques enables the development of more effective defensive measures for modern enterprise infrastructures.